Question

Gramps,

I was studying about the endowment ceremony and read that between 1845 and 1930s an “oath of vengeance” was performed as part of the endowment. My question is, how could this be part of the gospel of Jesus Christ?

Nick

Answer

Dear Nick,

Let me first rehash a bit of history for the benefit of some of our readers who may not be as familiar with the history as you are. (This will be a little long, so please bear with me!)

Background on LDS temple ceremony

Our modern temple ceremony evolved very gradually throughout the early history of the Church. Most of the core for the current initiatory ordinances was revealed in 1836 in Kirtland. During the last three years of Joseph Smith’s life he developed not only the concept and ritual of eternal marriage (and its corollary, plural marriage), but the idea of a further “endowment” that presented a series of ritual covenants in the context of an instructional narrative about man’s role and destiny in the Plan of Salvation.

During Joseph Smith’s lifetime the endowment was administered only in secret to a select circle of Smith’s most trusted friends—the “anointed quorum”, as they took to calling themselves. After Joseph’s death, when work had sufficiently progressed on the Nauvoo Temple, an “organized and systematized” version of the endowment became available to a major portion of the Church membership. Endowments for the living were performed in the temple beginning in late 1845 and continuing for a period of about three months.

The Nauvoo endowment was, to some degree, tailored to the society and circumstances in which it was revealed. It had to be vivid and memorable, because those who received it could not expect to ever repeat the ceremony (first, because there was no such thing as proxy endowments for the dead–these would not be authorized until 1877–and second,  because the Church was already planning to abandon Nauvoo and its temple). The Nauvoo endowment couldn’t presume that its participants were either literate or particularly knowledgeable about scripture (although certainly most of the participants were). In that context it made sense to present the endowment using some of the same pedagogical techniques that were commonly used in other social, religious, and instructional settings across frontier America. These techniques included dramatic acting, specialized clothing, travel between rooms, the affiliation of certain concepts with particular body motions or gestures, oaths of secrecy, and—I would suggest—some measure of rhetoric specifically calculated for shock value. The overall presentation of the Nauvoo endowment seems to have taken about six hours.

because the Church was already planning to abandon Nauvoo and its temple). The Nauvoo endowment couldn’t presume that its participants were either literate or particularly knowledgeable about scripture (although certainly most of the participants were). In that context it made sense to present the endowment using some of the same pedagogical techniques that were commonly used in other social, religious, and instructional settings across frontier America. These techniques included dramatic acting, specialized clothing, travel between rooms, the affiliation of certain concepts with particular body motions or gestures, oaths of secrecy, and—I would suggest—some measure of rhetoric specifically calculated for shock value. The overall presentation of the Nauvoo endowment seems to have taken about six hours.

The Nauvoo endowment seems not to have followed a written script. So far as is known, the first written text for the endowment was produced in preparation for the dedication of the St. George Temple some thirty years later; and it has been further refined numerous times since then. Nor, for obvious reasons, are “official” scripts for any variant of the endowment generally available. To try to get an accurate idea of what the Nauvoo endowment was like, historians have to turn to a variety of exposes written by ex-Mormons who had participated in the ceremony and then left the Church. While individual accounts often have reliability issues and are prone to hyperbole, they do provide a cluster of data points that overlap enough for historians to conclude that the 1845 endowment incorporated a provision now dubbed the “oath of vengeance”. There is disagreement about the specific verbiage of the oath, but the gist seems to be that the Church member would covenant to pray to God to avenge the deaths of the prophets upon the United States and to teach his or her children to pray for the same thing. This oath apparently remained in the temple endowment until around 1927, when it was removed as part of a general “good neighbor policy” implemented by the Church as an attempt to more fully integrate its membership into American life. (For more information on the development of the LDS temple rites presented in a faithful and respectful way, I highly recommend Jennifer Ann Mackley’s Wilford Woodruff’s Witness: The Development of Temple Doctrine.)

From fact to speculation

Now, what do we make of this? To be sure, it seems very out of place with the Gospel of Jesus Christ as it is popularly taught and understood within the Church today. Having convinced you to read this much of my response, let me make a confession: I don’t have a direct “answer” for your question. What Elder Oaks once said about trying to extrapolate reasons for unexplained revelations or policies, is also true when we try to come up with explanations for specific features of temple ceremonies whose content, origins, and meanings the Church pointedly refuses to discuss:

“If you read the scriptures with this question in mind, “Why did the Lord command this or why did he command that,” you find that in less than one in a hundred commands was any reason given. It’s not the pattern of the Lord to give reasons. We [mortals] can put reasons to revelation. We can put reasons to commandments. When we do, we’re on our own. Some people put reasons to the one we’re talking about here, and they turned out to be spectacularly wrong. . .Let’s don’t make the mistake that’s been made in the past, here and in other areas, trying to put reasons to revelation. The reasons turn out to be man-made to a great extent. The revelations are what we sustain as the will of the Lord and that’s where safety lies.” (Dallin H. Oaks, Life’s Lessons Learned [2011], 68–69)

Now, having confessed that I don’t have an answer for you; perhaps I can share some responses that have helped me, personally, reconcile myself to this jarring bit of Church history. I would probably broadly categorize my responses into three fields: historical, sociological, and theological.

Historical observations

First, a few historical insights. The author L.P. Hartley once observed that “the past is a foreign country; they do things differently there”. Barely twenty years after the oath of vengeance was incorporated into the Nauvoo endowment, Abraham Lincoln would suggest in his second inaugural address that the Civil War was divine retribution for the national sin of slavery:

If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from thosedivine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him? Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.” (Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address)

Whatever we may think of the oath of vengeance now; contemporary Americans—and really, even modern Americans who still revere Lincoln—seemed to accept the general idea that a generally loving God could still exact a terrible vengeance from a nation that had perpetrated a grave national sin.

And we should be very clear in our understanding that, so far as the Church was concerned, the American government had perpetrated a terrible national sin not only against the Smith brothers, but against the people of God generally. The Church had been thrown out of Missouri by a campaign of violence, theft, and rape culminating in judicial and gubernatorial fiats that the United States government refused to redress. Seven years later Joseph Smith was lured out of Nauvoo to his death by Illinois governor Thomas Ford, who had unilaterally overruled the judicial proceedings already in progress at Nauvoo with a demand that Smith present himself at Carthage–but who then, when informed of irregularities in the Smiths’ Carthage court proceedings, declined to intervene in the judicial process. There were rumors, never completely debunked, that Ford had explicitly green-lit Smith’s murder; and it was certainly Ford who ordered the only neutral state militia unit—the McDonough County contingent—out of Carthage on the morning of Smith’s assassination.

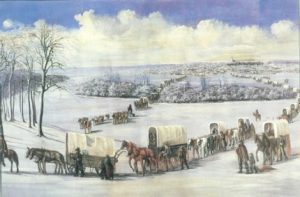

Adding insult to injury was the evacuation of Nauvoo. While recently-published Council of Fifty minutes suggest that it was always Brigham Young’s plan to have at least some Church  members begin the trek west very early in 1846, it is also true that the evacuation was hastened due to rumors spread by state officials that the United States Army was planning a summer campaign against the Mormons. This haste led many Church members to leave Nauvoo in the dead of winter without proper preparation, which in turn led to hundreds of miserable deaths in Iowa throughout the ensuing year—and those who were too poor to leave Nauvoo were subjected to a grueling siege the following September. Ten years later, comparable rumors and actual depredations would lead to the national crisis still remembered as “bleeding Kansas”; whose death toll would be significantly lower than that suffered by the Latter-day Saints through violence, exposure, and disease.

members begin the trek west very early in 1846, it is also true that the evacuation was hastened due to rumors spread by state officials that the United States Army was planning a summer campaign against the Mormons. This haste led many Church members to leave Nauvoo in the dead of winter without proper preparation, which in turn led to hundreds of miserable deaths in Iowa throughout the ensuing year—and those who were too poor to leave Nauvoo were subjected to a grueling siege the following September. Ten years later, comparable rumors and actual depredations would lead to the national crisis still remembered as “bleeding Kansas”; whose death toll would be significantly lower than that suffered by the Latter-day Saints through violence, exposure, and disease.

Under the circumstances and overall attitudes prevailing in mid-nineteenth century America, I think it remarkable that the Mormon pioneers were able to avoid the sort of wholesale violence that erupted in Kansas and then consumed the rest of the country during the American Civil War. I am inclined to wonder whether the “oath of vengeance” actually provided a sort of safety outlet for the raw emotions resulting from the nation’s shoddy treatment of the Mormons, by ritually assuring Church members that vengeance would eventually come while similarly ordaining that it must come through prayer and not through war.

Statistical evidence of violent crime during the Utah Territorial period is hard to come by before the 1880s, but anecdotal evidence suggests that extralegal violence was (sensationalized anecdotes aside) relatively rare; and statistics from the 1880s suggest that Utah was one of the least violent of the western territories and states. Similarly, while the  1857 Mountain Meadows Massacre represents a horrifying act of violence perpetrated by a rogue local militia unit consisting entirely of Mormons; the Church’s overall military campaign against the federal Utah Expedition that same year are singular for their efforts to avoid taking human life. And the Mormon detail left to watch over the emptied homes in Salt Lake City as Johnston’s Army entered the city demonstrated extreme restraint (the federal troops marched through the city singing a filthy marching song about a soldier who violates a girl and then sodomizes her father, kills him, skins him, and nails his skin to the outhouse door). Progressing into the 1870s and 1880s, it seems extraordinary to me that any people would put up with having their men routinely imprisoned, women and children forced to testify against their husbands and fathers, and their properties confiscated without breaking into full-scale revolt; and again, I wonder what the oath to leave justice to God may have had to do with the Saints’ ability to keep the peace and reconcile themselves to the monumental surrender that the Manifesto of 1890 represented.

1857 Mountain Meadows Massacre represents a horrifying act of violence perpetrated by a rogue local militia unit consisting entirely of Mormons; the Church’s overall military campaign against the federal Utah Expedition that same year are singular for their efforts to avoid taking human life. And the Mormon detail left to watch over the emptied homes in Salt Lake City as Johnston’s Army entered the city demonstrated extreme restraint (the federal troops marched through the city singing a filthy marching song about a soldier who violates a girl and then sodomizes her father, kills him, skins him, and nails his skin to the outhouse door). Progressing into the 1870s and 1880s, it seems extraordinary to me that any people would put up with having their men routinely imprisoned, women and children forced to testify against their husbands and fathers, and their properties confiscated without breaking into full-scale revolt; and again, I wonder what the oath to leave justice to God may have had to do with the Saints’ ability to keep the peace and reconcile themselves to the monumental surrender that the Manifesto of 1890 represented.

Sociological observations

From a sociological perspective, the “oath of vengeance” also may have played a role in helping Mormonism to keep a distinct social identity during a time of increased national integration after the Civil War. LDS sociologist Armand Mauss has written about how much of LDS history has, whether deliberately or unconsciously, resulted in a sort of “optimal tension” between the Church and the broader society in which it existed. The basic idea is that if a sub-culture is too different from the overall culture, it engenders so much hostility as to create a degree of opposition that threatens its very survival; but if the subculture blends into the overall culture too well, the subculture loses its sense of purpose and evaporates into the larger culture.

Applying this theory historically, we know that as transcontinental railroad and telegraph lines were completed in the 1860s many opponents of Mormonism fondly hoped that Utah’s commercial, political, and intellectual integration into the broader American community would prove Mormonism’s undoing. As the Church eventually discontinued the political, commercial, and theological practices that had brought it so much legal opposition, young Mormons of the late 19th and early 20th centuries would naturally be entranced with the media, fashions, money, and culture of the eastern states. Temple covenants—especially the oath—would have reminded them of the need to remain spiritually and, to some degree, materially independent from a broader society that had rejected their values and was perennially ready to take up arms against any Mormon who got out of line. While the Manifesto demonstrated that Church members were to submit themselves to secular political authority and seek to be good citizens of whatever nations they lived in; the temple reminded Mormons that they were first and foremost as citizens in God’s kingdom and members of a Zion society-in-exile (a point that Church critics at the Reed Smoot confirmation hearings thoroughly understood).

This sense of detachment from secular culture and political authority was (and, to a lesser degree, still is) also reflected in LDS hymns such as “O Ye Mountains High”, “Ye Elders of Israel”, and “Praise to the Man”. As an interesting tidbit of historical trivia, the line in “Praise to the Man” that currently reads “Long shall his blood which was shed by assassins/plead unto heav’n” originally suggested that the Prophet’s blood would “stain Illinois”; the verbiage was changed to “plead unto heav’n” as part of the good-neighbor policy referenced above. Even so, other aspects of LDS culture such as the Word of Wisdom, family home evenings, and temple garments may serve today to maintain the same sort of “optimal tension” that Professor Mauss describes.

Doctrinal observations

Having looked at some of the history, I’d like to wind up by reconsidering some of our theological presumptions about what “the Gospel of Jesus Christ” is, what it represents, and what sorts of actions it entails. Modern discourse about “the Gospel” often reduces to Christ’s universal love, His message of forgiveness, and His invitation that all people everywhere come to Him and be saved. This is, in my view, absolutely correct. As members of His Church and heirs to the covenant of Israel, our eternal commission is to forgive all men their trespasses against us; and our current injunction is to rescue as many of our erring brothers and sisters as we can.

But we know that not all humankind will accept that invitation. We know, from statements by President Brigham Young and Elder Heber C. Kimball, that at some point the Church will bring its missionaries home in anticipation of a day when the Lord will preach His own sermons and the calamities the Lord has warned against (D&C 1:17) will finally come to pass (see also D&C 133). Part of that, our scriptures tell us, involves the notion of God’s somehow “avenging” the sufferings of the righteous. These ideas don’t just turn up in the Old Testament (as in the so-called “imprecatory” psalms such as Psalm 69). The New Testament reiterates this quite a bit–you can look at, for example, Revelation 6:9-11; 2 Thessalonians 1:7-8; the entire book of Jude (it’s short); Luke 21:22; and Luke 18:7. In the Book of Mormon, Abinadi’s dying testimony warned his murderers of the potential for divine retribution (Mosiah 17:19); and the notion of innocent blood crying out from the ground for vengeance appears repeatedly in the Book of Mormon (for example, in Alma 37:30, Ether 8:22, Mormon 3:15 and Mormon 8:20).

With that being said, the New Testament seems clear that because God Himself will take vengeance, as Christians we are forbidden from doing so. See, for example, Hebrews 10:30 and Romans 12:19. And while the Doctrine and Covenants does set out a pattern for using violence in self-defense after extreme provocation as outlined in D&C 98 (a pattern referred to in justifying the deployment of Zion’s Camp in D&C 103 and 105); the one hundred thirty-fifth section–which specifically deals with the deaths of Joseph and Hyrum Smith–explicitly leaves retribution to the Lord when it proclaims that “their innocent blood, with the innocent blood of all the martyrs under the altar that John saw, will cry unto the Lord of Hosts till he avenges that blood on the earth.” (D&C 135:7)

Closing thoughts

In closing this, Nick, I want to thank you for sticking with me thus far; and also let you know that I struggled to make this answer shorter and more digestible. But it’s just not an easy topic, because the oath arose when such a different worldview prevailed. There has been an enormous amount of change over the last hundred and eighty years both in our modern western culture generally and in the way we, as Mormons, talk about specific theological issues. I believe that these cultural changes underscore the need for living prophets and apostles who are commissioned to preach the gospel and administer in the ordinances thereof: liturgies, teaching techniques, and rhetoric that resonated with individuals and tended towards the establishment of a Zion community in one generation, may leave the next generation feeling hollow and even alienated. As a product of twenty-first century American culture, I can be personally uncomfortable with the verbiage of the “oath of vengeance” while still being open to the possibility that it served a particular purpose in the time and place in which it was administered. My own belief, subject to the caveats about speculation that Elder Oaks has provided, is that like other elements of the temple ceremony the oath was inserted into the endowment by divine inspiration and was removed when it was no longer effective to the rising generation.

To the degree that this issue still creates some discomfort I would encourage you to take some more time with it. FairMormon has an article on this issue that brings up some aspects I haven’t really gone into here; and you may find them helpful. And please do dive into the scriptures that I’ve cited above, because in my own experience there’s no substitute for really wrestling with the scriptures and trying to understand them on their own terms. That process has often prepared me to receive revelations that sometimes bring answers, and always bring peace and confidence.

Warm regards,

Gramps